Reliability Engineering - Stop Trying To Make Pagers Happen!

A common misconception about reliability is that it's mostly about pagers and on-call duties. This blog explains why this is wrong, and what to do instead.

Aug 6, 2023

Benny Cornelissen

Cloud Consultant

At Skyworkz we get to work with industry-leading clients and as a result, we get to work on a fair share of high-volume, mission critical systems. The kind that has to be available for >99.9%. But this blog isn't about some fancy technology, masterful hackery, or the next big thing in Cloud. It's not even about AI or LLMs, which is rare these days. I'm even writing this myself. Oldschool. Maybe even boring. It seems fitting, given today's subject: Reliability.

Reliability isn't the most fancy topic, but for our clients, it's an essential topic. Shiny features won't make you money if your systems are broken all the time. And some systems are simply too essential. Reliability matters for a business' bottom line, and in some cases unreliable systems may even have legal implications.

For many companies, discussing reliability means getting 'non-technical' people involved. Stakeholders with different perspectives looking to reduce risk, ensure compliance, or optimize revenue: Product Owner, Business Owner, Security & Risk, Business Continuity Management, and even Legal.

Typically, all those stakeholders agree on one thing: we want our systems to work as intended all the time.

Availability meets Reliability

A very common approach that I've seen at many companies is to center the discussion around availability. We want our systems to work as intended as much as possible, so availability of our systems is key. That sounds like a pretty fair statement.

In practice, this usually means that the stakeholders will focus on establishing a desired service level. Let's take an example system called "Hermes". Hermes is a logistical system that takes the information of sorted packages from a sorting facility and calculates the most efficient route for a delivery courier to drive. This logistical process is used every day, deliveries are made anywhere between 07:00 and 23:00, and the parcel sorting facility works 24x7. Our stakeholders get to work on establishing the service level for Hermes.

Desired availability: 99%

Desired service window: 24x7

Time-to-Fix / Recovery Time Objective (RTO): less than 60mins

Recovery Point Objective (RPO): less than 8 hours

Our example system above needs to work around the clock, and when it breaks it needs to be fixed within the hour. So our stakeholders will move on to define desired mitigation strategies, which typically look somewhat like:

System is deployed in a high-available fashion (at least 3 replicas) on our production Kubernetes platform

Persistent data (e.g. databases) is to be snapshotted every 4 hours

System is added to on-call rotation

The stakeholders are quite happy with the result. The mitigation strategies allow for a failing Pod or even a node, it's possible to restore recent-enough data, and there's someone to take action quickly at all times. In fact, after running Hermes like this for 3 months, it achieved 99.3% availability. The RTO and RPO were also never breached. Happy emails were exchanged, and the Product Owner treated their team to cake.

Availability != Reliability

The desired service level for Hermes was clearly created with availability as a priority. But while the Hermes team was having cake, both Bob and Susan were writing less-than-happy emails to their managers. Bob is an engineer on the SRE team and had just been on-call for a week, during which he had to manually revive Hermes 5 times. A 6th time, one of the supporting microservices failed, and he couldn't quite figure out what went wrong as the on-call playbook hadn't been updated to include that microservice. Bob tried calling the developers on Team Hermes, and eventually one of them picked up the phone. After multiple broken nights and a wasted Saturday, Bob is fed up with Hermes' lack of reliability and wants his manager to escalate. He feels the Hermes team needs to focus on building more reliable software, and he wants them to be on-call for it until the issues are addressed. "We're doing DevOps here, right? They build it, then they should run it".

Susan wasn't too happy either. Susan is a Planning Supervisor and got to deal with two dozen couriers who couldn't deliver their packages since they had no route information for 45mins, and while Bob was trying to get hold of a Hermes developer, there was nothing she could do except wait, while the flow of packages through her facility gradually came to a stop.

So while Hermes achieved its desired availability, it wasn't perceived as reliable.

It's not just about Availability

So what's the deal here? Well, Hermes' availability number wasn't too ambitious to begin with (so fairly easy to achieve, even through sheer luck). But to achieve it, Hermes had to rely on someone to manually revive it regularly. And even worse, the person responsible for doing just that didn't have the necessary information or training to do it. Communication was lacking as well.

However, none of these factors are really considered in the desired service level definitions mentioned earlier. Hermes is showing many signs that reliability is lacking, but none of them are a 'business concern'.

Defining Availability and Reliability

Our current service level focuses primarily on the Availability of Information (from the CIA Triad), from which we get a Desired Availability (percentage), and from there we typically calculate the RTO. This view is too simplistic, and a little one-dimensional. Let's improve our definitions, so that we can also measure the right things, and make sure that when reliability is lacking, it does become a business concern.

When do we consider our system available?

Coming up with a percentage is easy, but it's not very useful unless we define what availability actually means.

Availability defines whether a system is able to fulfill its intended function at a point in time.

This means we need to specify:

What is the intended function of the system?

How well should the system perform the function?

At what time does it need to perform the function?

Error budget: how much failure do we accept?

Let's take a simple example. You install a light next to your front door, so that you can find the lock when you arrive home late at night. Therefore:

Intended function: provide light for the front door area of your house

How well should it perform: the light should illuminate the entire front door area, with an intensity of at least 300 lumens

At what time: when it's dark outside

Error budget: it needs to work 99.9% of the time

This means our system is considered unavailable if the light doesn't work at all, when it isn't bright enough, or when it illuminates the wrong area. It also means we don't really care about the light during the daytime, and it also means we have a sliding service window that changes with the seasons. On second thought: we now need to define what 'dark' even means, and think about things like solar eclipses.

Reliability and Error Budgets

The percentage for availability defines your budget for 'availability error': how much time can your system fail to perform its intended function? But as we've seen with Hermes, that's not the whole story.

Let's add a couple of new concepts:

Mean Time Between Failures (MTBF) -- how often does it fail?

Mean Time To Recover (MTTR) -- how long does it take to fix it?

There are some other concepts we can add to this list later, but these are the ones you should start with.

These concepts all matter in 3 different ways:

Defining Acceptable Level (SLO)

Measuring long-term performance

Measuring short-term performance

A decreasing MTBF indicates a system that is becoming less reliable. An increasing MTTR indicates that a failures become harder to fix. In the case of Hermes, we can safely assume that the Acceptable MTBF should be way higher than it currently is, while MTTR is negatively affected by a lack of documentation and availability of trained/knowledgeable staff. But similarly, poor or non-existent logging or a complicated codebase may negatively affect MTTR.

If your landscape is designed to automatically recover failed workloads (for example when using Kubernetes to orchestrate containerized workloads), it's good to split up MTBF into separate categories:

Mean Time Between Failures (MTBF), for all failures regardless of how they are handled

Mean Time Between System Incidents (MTBSI), for failures that require human intervention

In case of Hermes, Bob had to manually revive it 5 times over the course of a week, which is obviously bad. However, if a all Pods for a Hermes Kubernetes Deployment crashed and would simply be restarted without waking up Bob, nobody might have noticed (even if Hermes was unavailable for a minute). In both cases the failures would count against the MTBF, but in the case of Kubernetes handling the failure it wouldn't count against MTBSI.

On-call is not there to fix your lack of reliabilty

The classic view on Availability typically specifies On-call as one of the default measures to ensure availability. This makes sense, when you look at things from a pure Availability perspective. Having someone on-call means someone starts fixing the issue sooner, which reduces the MTTR for out-of-office-hours failures and means it's easier to achieve your desired availability.

But if we're being honest about our reliability, On-call does nothing for that. Bob restarting Hermes 5 times made for a healthy MTTR, but the MTBF didn't lie. Hermes is failing quite often. Also, Bob is feeling quite unhappy right now.

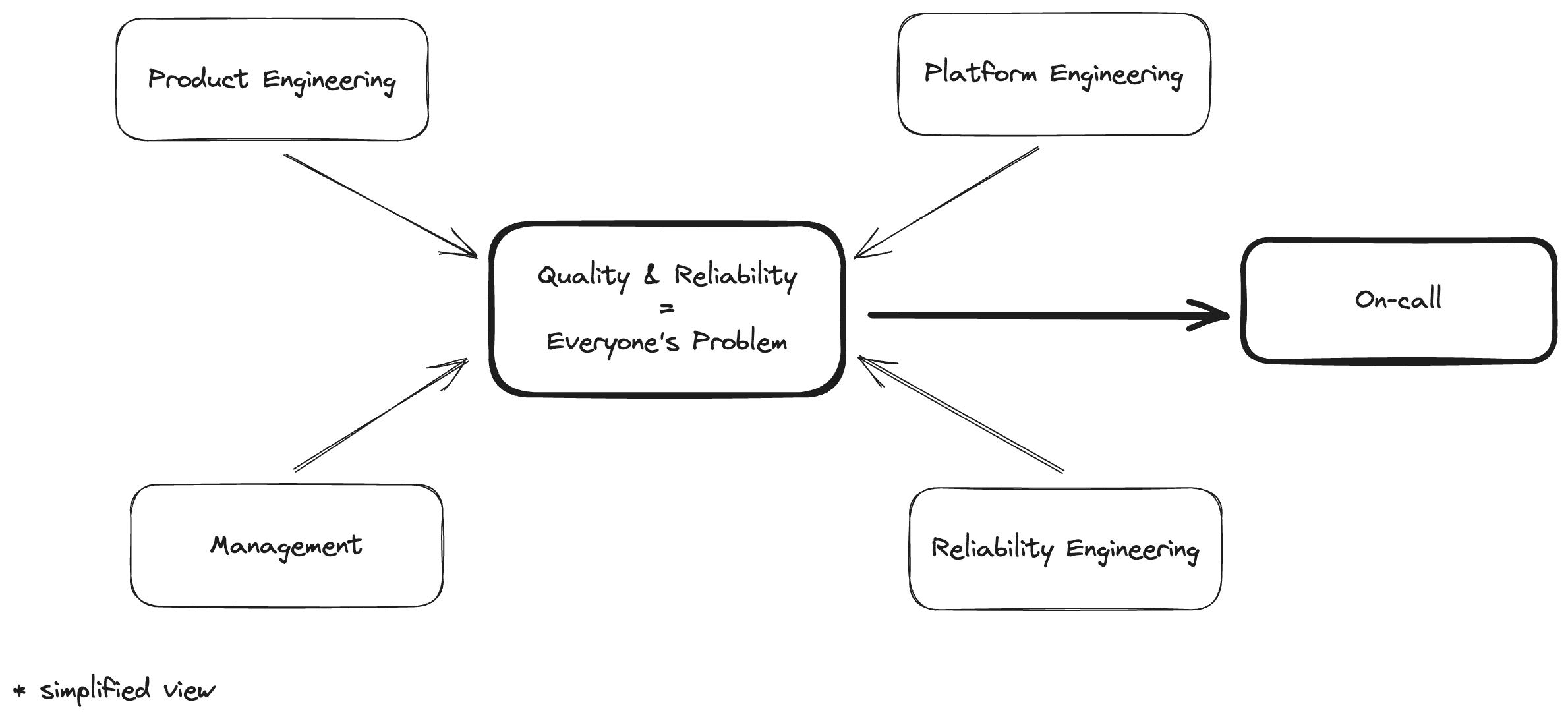

Reliability is everyone's problem, but shouldn't be On-call's problem.

Stop trying to make pagers happen

When focusing on building reliable systems, you should be viewing On-call as an insurance policy for a residual risk that has a high impact, but otherwise low probability. On-call is there for when, despite all your efforts to build a great system, it still broke and it needs to get looked at.

So your starting point for building a reliable system is: how do I eliminate the need for on-call? How do I minimize my residual risk to the point where I don't need the insurance? Think about what kind of availability you need, and what kind of robustness is needed to get there. Consider negative changes to your MTBF or MTTR as clear signals to review your team's priorities. And always consider: is it really necessary to wake up someone for this?

Stop trying to make pagers happen. They shouldn't happen.